Matinicus: Part 1

Check In

I flew to Matinicus Isle, Maine at sunset the Friday before Columbus day. Matinicus's airstrip doesn't have lights and only small aircraft can touch

down there. Before take off I tried to text a picture of the plane's Penobscot Air logo to my mom, but my phone died. Fitting, since cell service is

spotty on the island.

Located twenty miles off the Maine coast and accessible only by boat and plane, Matinicus has no grocery store, no paved roads, no doctor, and no police

force. About twenty people live there year-round and maintain a school, post office, and power station. On the flight over I looked down at

granite outcrops turned pink by the setting sun and a cold blue sea. Two women flew with me, one of whom offered me a ride in her friend's pickup to

my hotel, Tuckanuck Lodge.

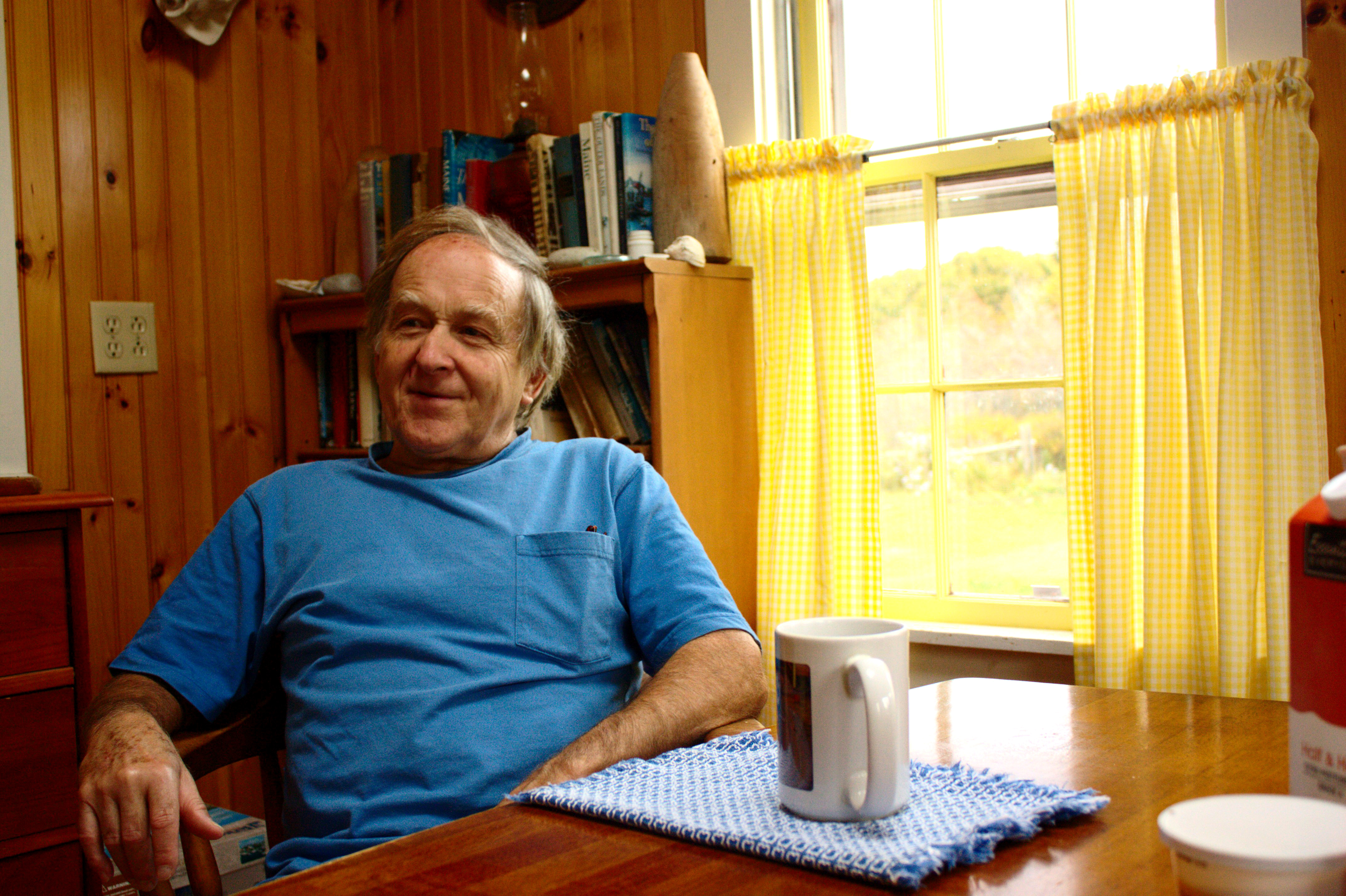

The owner, Bill Hoadley, and his dog Sandy met me out front. Bill cooks his guests dinner for an added fee each night (breakfast is included;

you're on your own for lunch), and dinner is at seven. No exceptions. His Lodge is an old residence he bought thirty years ago and

renovated over a span of ten years. He shuns computers and TVs and the only phone is a forty-year-old rotary. A desk in the study seems to contain

his entire life: bills, guest names and addresses, family photos, a book he wrote about growing up on Nantucket. He says living alone is bearable

but only if he has a dog, specifically a female mixed breed (they're the most docile). A cabinet shelf in his kitchen is full of coffee mugs

emblazoned with pictures of other dogs he used to own. At 7am Bill plays classical music throughout the house to wake his guests for breakfast, but I'm

gone by then. I went to see the harbor.

Stragglers

Unlit gravel roads criss-cross Matinicus, so when a vehicle approaches in the dark it becomes your entire focus. Sounds like an engine revving and pebbles

crunching under tires are explosive in the morning silence. I shrink off the road and onto someone's front lawn to make room, averting my

eyes from the headlights. Once the truck passes (everyone has a truck), the only sound is a ringing buoy marking the harbor

entrance. This sound is simultaneously haunting and fragile, audible throughout the island. Soon it's interrupted as lobster boats start their motors and

troll around before heading off for the day. It's 5:45 and these are the stragglers. A mangled lobster trap rests ten feet above the high tide line, a victim

of the wind and waves.

Ropes, traps, and buoys are everywhere, some even abandoned in the woods. No one seems to abide by any particular property boundaries and footpaths

cross straight through strangers' backyards. Lobstering crew (sternmen) live here in shacks which lean out over the water on fifteen-foot-high

wooden stilts. Some sheds are so primitive they lack running water, although most have modern amenities. Today is a calm day and most lobstermen

will finish their seasons before the weather gets rough, retreating to their summer homes in Florida. A few stay on the island and fish all winter, braving

the elements.

Back to the Earth

At breakfast, Bill tells me about past guests, his childhood on Nantucket, people on the island, people on the mainland, the history of Matinicus, and

so on. Sandy watches us eat and begs for a bite of cantaloupe, which Bill gives her. He mentions there's an abandoned house on the next property that I

might find interesting. It's a one-room cottage, painted white, and overgrown with grass and shrubs. The front door is only accessible because sternmen have

picked their way through to take and reuse kitchen appliances.

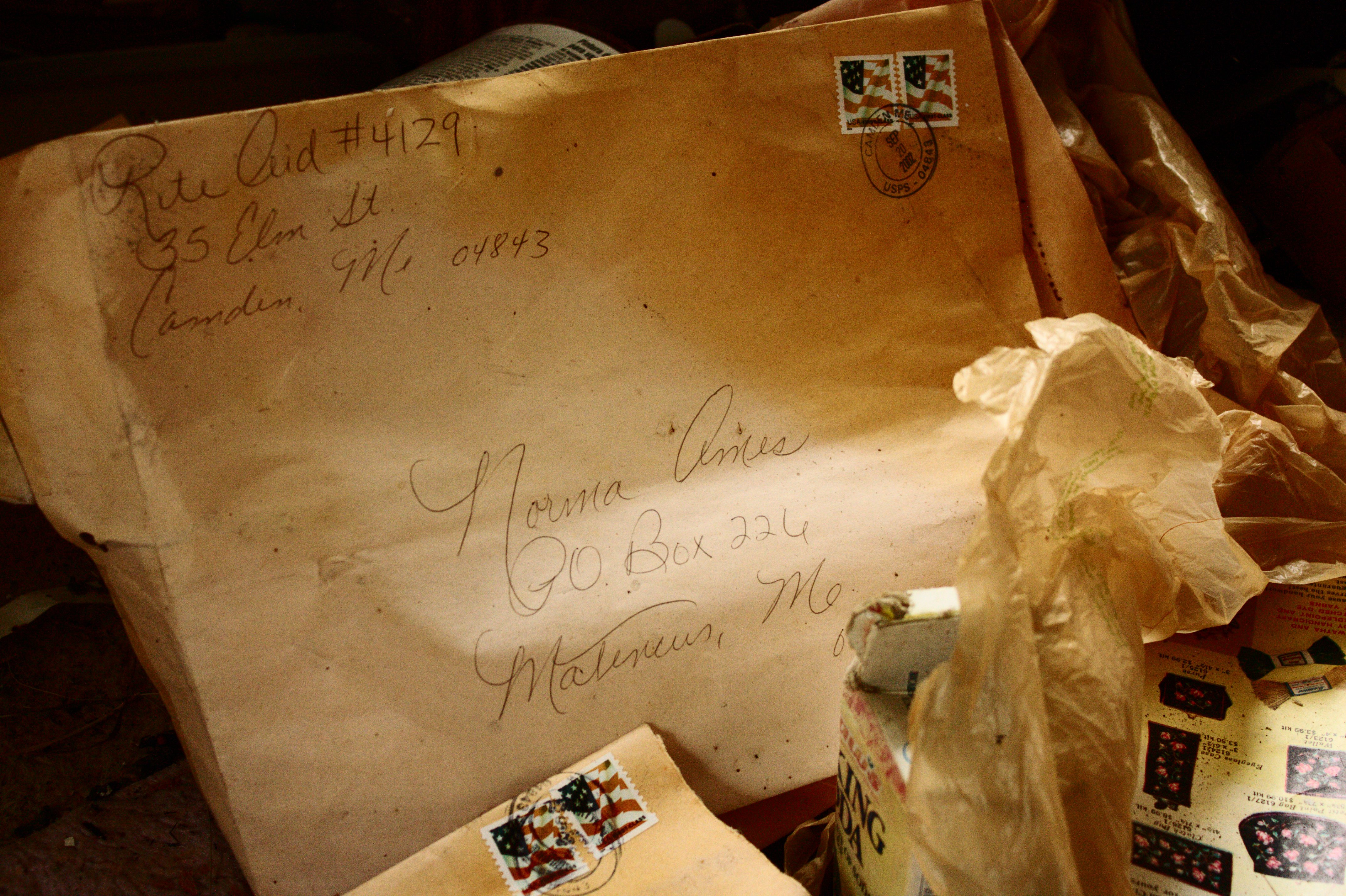

Inside, the house is ransacked and the owners' personal effects are thrown everywhere. From old envelopes, report cards, and prescription bottles I find out

that Norma and Gilbert Ames used to live here. Their wedding cake topper is still in the cupboard. Ames is the biggest family on the island and one of

the oldest. In spring, the lobstermen meet to discuss who gets to fish the bottom around Matinicus and who doesn't. Territorial disputes are common in these

waters; they're the best lobstering grounds in the world. The Ames' typically hold sway and fishing is confined to locals only. Outsiders' traps are cut.

Later I find out that Norma had a fatal stroke in 2003 and Gilbert died soon after in 2005. They owned a flock of ducks. Bill claims that when Norma died,

Gilbert's kids came to take him away. Before he left he shot the ducks, one after another, and left their carcasses laying outside the

cottage. I eye the sagging ceiling anxiously and decide it's time to leave. Soon this place will collapse and return to the island. Gilbert and Norma Ames

are buried next to each other not far away.

Sound Absorber

Much of the island is made up of open fields covered in grass, flowers, and brambles. Apple trees from abandoned orchards are everywhere and produce a

small, thick-skinned, sweet and sour fruit. Spruce forests began to regrow fifty years ago after farming was abandoned and inhabit about one fifth of

the island. Now they're dying from beetles. The forest floor is carpeted in thick moss which soaks up water and sound like a sponge. My breathing was the

loudest sound, so I held my breath for awhile.

The island has two long beaches, "North Sandy" and "South Sandy", and several bits of rocky shoreline. Sand dollars, gigantic mussels, clam shells,

seaweed, and buoys wash up everywhere and the water is so cold it hurts my feet. Most of the summer residents left a few weeks ago, so I'm alone during

my walks.

The Sternmen

One afternoon, after reading for a few hours on North Sandy, I start back toward the lodge and run into a sternman. He's

done for the day and offers me a beer from his cooler. We chat in the middle of the road. Soon a small group of other sternmen joins him, and they start

talking about their experiences (like fishing in winds so strong the Coast Guard relinquished responsibility for their safety). Drugs of all kinds are

prevalent, even out here. So is alcohol. People get bored and fight sometimes ("It's like high school") and are dealt with by their peers ("There's no

law out here; we decide who gets punished and how"). Superstitions abound: one guy refers to the year 2013 as "two thousand twelve plus one". Overall

this is a group of hard working men and women, mostly young, doing a dangerous and high-paying job in a remote place. They offer to take me on a boat ride

the next day so I can photograph them fishing, but I'm leaving in the morning. I guess I'll have to come back next spring.