Chapter 1 Section 1

A Brief Introduction to Neurons

This first section is deceptively math-free and covers some basics about neurons. We’ll need to know these basics if we’re to understand the onslaught to come!

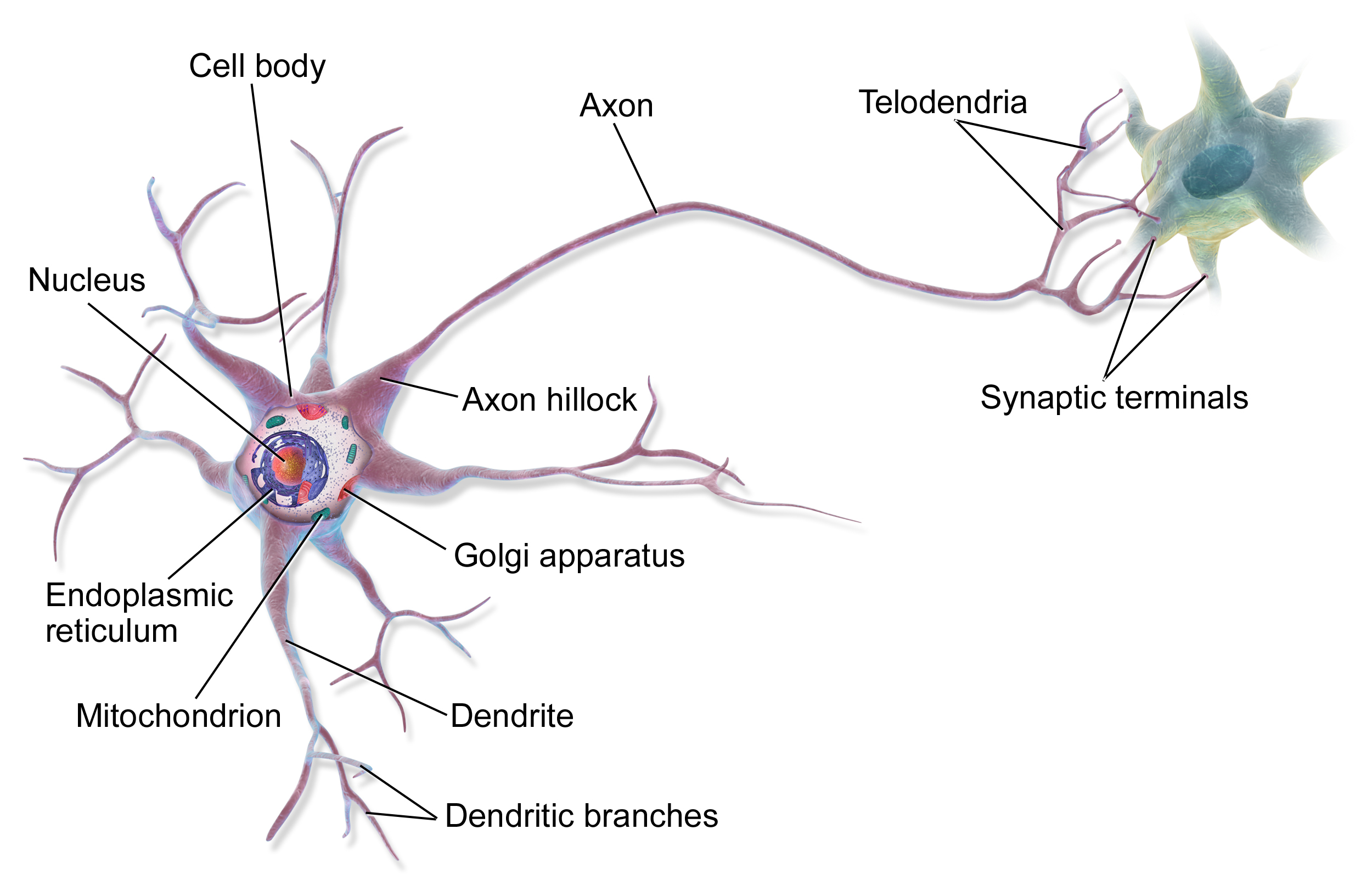

Neurons are cells that generate and propagate electrical impulses in response to stimuli. Impulses enter the neuron through its dendrites, travel along its axon, and trigger the release of neurotransmitter chemicals at its synaptic terminals. Dendrites are long, slender branching structures which extend from the soma, which is the center of the neuron and contains its nucleus. The axon is a thicker long structure which terminates in shorter branches.

Different types of neurons possess dendritic trees of different sizes, from thousands to hundreds of thousands of inputs (which each branch is an input). Axons connect to hundreds or thousands of other neurons and can range in size from a few millimeters to the length of the human body.

Ion channels - think of them as tunnels through which charged particles can move in response to certain environmental forces - dot the neuron membrane. Calcium (Ca2+), chloride (Cl-), potassium (K+), and sodium (Na+) ions play a prominent role. The differences between their concentrations inside and outside the neuron create an electrical potential (voltage) accross the neuron membrane. Changes in their concentration and in that potential activate ion channels and allow them to cross the membrane, further changing their concentration gradient and the electrical potential.

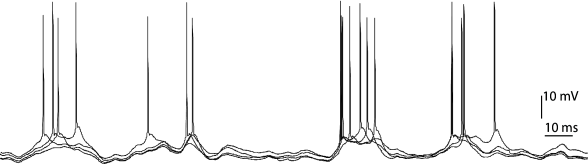

At “rest”, the voltage accross the membrane from outside to inside is -70mV. The inside of the neuron is polarized relative to its surroundings. When negatively charged ions flow into the cell or when positively charged ions flow out, the voltage drops further (hyperpolarization). When negative ions flow out of the cell or when positive ions flow in, the volage increases (depolarization). If we depolarize the neuron to the point that its inside is at a voltage of 100mV compared to its surroudings, this triggers an action potential, which is actively propagated down the axon to the synaptic terminals.

Once an action potential has occured (the neuron has “fired”), the neuron will enter a refractory period of tens of milliseconds during which it cannot fire. As action potentials reach the synaptic terminals they trigger the release of neurotransmitters into a space between the axon of this neuron and the dendritic branch of another. That space is known as the synapse. Neurotransmitters can either excite the next neuron or inhibit it via depolarization or hyperpolarization.

If we want to understand how neurons react to stimuli, we have to measure these electrical impulses. Measurements can be taken outside the neuron (extracellular) or inside it (intracellular). Intracellular measurements involve placing a very thin hollow glass electrode filled with a conducting electrolyte into the neuron. Its recorded electrical potential is compared to that of a reference electrode placed nearby. Extracellular measurements capture weaker signals as they are taken farther from the neuron where the electrical pulse is weaker. Measurements are usually made at the soma and measurements from axons and dendrites are harder to come by. Intracellular recordings are typically done in-vitro (think petri dishes) whereas extracelluar recordings are taken in-vivo (inside of a living creature). This isn’t always the case, just usually.

Even though we can measure action potentials (“spikes”), it’s difficult to understand how they relate to a specific stimulus. Neurons react to their own internal processes, those processes have a certain randomness associated with them, and experimental subjects are under various states of arousal and undergoing numerous cognitive processes. We can’t predict exactly what kind of response a stimulus will create and we will always measure a different set of spikes (or “spike train”) across different trials. So we instead try to predict the probability that a spike occurs within a given time interval. Much more on that later.

And that’s the intro! Don’t worry, much math to come. In the next section we’ll talk about how we measure firing rates, characterize the neuronal response, and predict average firing rates given a specific stimulus.